Evenly Spaced Rectangular Grids

March 2025

Alyosha’s home was filled with tired, sweating, dirt-laden peasants just off from a long day working the land. His home had always been the evening hub of the little village of Konevnya, a home where vodka was drunk, rumors were exchanged, and small deals and arrangements were made amongst the townsfolk.

This evening, the room was astir with rumors of a state official visiting from Petersburg in just two or three days’ time. Elders of Konevnya had received notice of this visit from The Department of Land Management, but very few details on what the visit was actually for.

“Perhaps to raise the damned grain tax again.”

“Or maybe they heard of our lean year and are coming to provide assistance?”

“Can’t be anything good.”

“Oh, don’t be silly. Our great Tsarevich has not done anything to wrong us. Bless him.”

“We will see, no need for us to worry in the meantime.” said Fyodor slowly and thoughtfully. Fyodor stroked his long, knotted white beard carefully with one hand, the other rested on a use-worn birch cane that was older than him. It was his father’s. The room was quiet for a moment as Fyodor thought to himself. When he talked, the town listened. “Enough idle chatter, let’s be off to our homes. We have Vespers tonight.”

For the next two days the village continued on as usual, but a curious apprehension certainly hung in the air as it waited for the visit from the capital. A typical day in Konevnya was busy and full but never rushed. Men toiled in the field—digging, watering, hoeing, planting, harvesting. Women toiled in the home and amongst the livestock—milking, feeding, mending, crafting, fixing, cooking. The children who were old enough to help did so and those who were too young were always watched and cared for by family or by neighbor. But all the while, everyone kept an eye towards the bumpy—and this time of year, muddy—dirt path leading out of town, waiting for the official from Petersburg.

Finally, one afternoon a little dot that was the carriage from Petersburg appeared on the horizon. Word spread quickly and by the time the mud-clad carriage was nearing the village center, everyone in town was peering out of windows, walking to the edge of fields, taking a break from their usual toil to see who Peter the Great himself had sent.

The official was seated in the carriage. He looked like a very tall man. This was accentuated by his awkwardly thin frame. He had dark black, shining hair, kept neatly combed to the side, and some scant facial hair attempting without much success to propagate itself. He had a boyish appearance, but was at the same time quite a serious looking figure.

Fyodor kindly waved down the carriage, slowly shaking the official documents from the Tsar’s office above his bald and wrinkled head.

“Why, hello, young man. Welcome to our little village, Konevnya. I am Fyodor.”

“Thank you, sir. I am Ivan Pavlovich, from the Department of the of Land Management. And your last name, Fyodor?”

“Oh, he-he. It’s just Fyodor.” The old man responded with a soft chuckle.

Ivan furrowed his brow in mild agitation. Why is he not telling me? Is he mistrustful of the Tsar and his ministries? Does he not have a last name? Ah, no matter.

“Let me, show you your accommodations, Ivan. Actually, you’ll be staying with Ivan! Fancy that, eh?”

Fyodor walked Ivan down a small dirt path to the corner of the village where most of the townspeople resided. He pointed out so-and-so’s home, so-and-so’s field, this tree, this grove and that, this person’s cattle, that person’s goats, and all that he thought would be relevant for the visitor as they walked. They reached the cabin. Fyodor gave it a knock and let himself in. Ivan’s wife and two of their youngest greeted the men as they entered.

“Matryoshka, this is Ivan. Good name isn’t it!” Fyodor bellowed. Matryoshka showed the visitor his quarters. Once he was settled in, had a cup of tea and a small plate of food from Matryoshka, he stated his simple-enough tasks for the next several days to Fyodor.

“Well, it’s simple enough, really. I am just here to observe the way you are doing things with respect to agriculture and animal husbandry here in Konevnya. After observing for a couple days, we shall gather the relevant townsfolk for a meeting. I’d like to discuss my observations and share some proposed reforms and directives from the Tsar aimed at helping you all with your approach to agriculture. Then I have some mapping and accounting to do, and I’ll be out of your way. Shouldn’t take more than three or four days.”

“I’ll let the townsfolk know your plans and arrange a meeting for all of us at Alyosha’s in two days’ time. Let me know if you need anything until then. Matryoshka will provide you with all your meals while you’re here. We are honored to have an official sent from our Father himself.” Fyodor bowed quite gracefully despite his crooked and creaking back and limped on down the street.

The next morning, Ivan busied himself around the village. Silently and stoically, he observed the men toil in the fields. He watched the women care for and milk the livestock. Seriously and quietly he observed the children help with the butchering of cows. For the entirety of the following day he gravely observed the cattle roaming various fields on the hills north of the main paths. The townsfolk chittered amongst themselves with great interest.

“He must be some expert in his field. Just look at how he observes the cattle for hours without stirring.”

“I hear he studied in Prussia for years before coming to his role.”

“Nonsense, how can a man that young, barely able to grow a beard, know much of anything. It takes generations to achieve our skill.”

“Oh, but how he keenly observed every detail of our meat processing yesterday. He must be quite intelligent.”

And so the musing continued, excitement and nervousness building up to the village meeting that night. Before Ivan came back from the cattle fields, the relevant men in town, congregated in Alyosha’s front room. Those parties not deemed relevant crowded quietly in the sleeping quarters, hoping to silently listen in on the meeting that was such a complete novelty to the little village of Konevnya.

Ivan opened the front door and had a little start, surprised at the number of men crammed into the tiny quarters.

“Oh…uh, hello, all. There are more of you here than I would have guessed. Happy you all came.”

Fyodor motioned for him to sit as men scooted over to make space for him on the birch bench, worn pleasantly smooth from generations of use. “Perhaps you have questions for us to begin with.” Asked Fyodor kindly, like a grandfather would.

Ivan looked down at his giant ledger quite seriously at a number of notes, figures, and diagrams he had jotted down over the course of his visit. “Well, yes. Thank you, Fyodor. Perhaps the first one is more out of curiosity than utility. But why is it that some of the cows don’t have horns? Are they deficient in a nutrient of some sort? Diseased in any way?”

Strained silence followed, broken by the soft giggle of a child who could not contain himself in the back room. A man next to Ivan charitably forced a cough to blanket up the child’s laughter.

“Those are heifers.” Said Fyodor, hoping to urge the conversation elsewhere, knowing now that this was not going to go anywhere near as he expected. Fyodor worried that any more questions like this from Ivan may provoke uncontrolled laughter, or indignation, or anger, or a beating, or a number of other undesirable outcomes, yet for the sake of his village, he wanted to find out about what the Tsar and his officials may want to do or change in Konevnya, and so he pressed on, “How about your more relevant questions, Ivan?”

“Oh, yes,” he looked down at his ledger, not realizing that he had asked such a question as to lose every shred of credibility that he had accrued with the townsfolk from his noble title and two days of enigmatic observation, “so who owns the rye field south of town? And the wheat field adjacent to it? And the cattle pastures to the north?”

A middle-aged man spoke up, “Well, I tend the far left strip of the rye field. But own it? No, I tend it. I have a plot on the rye field west of town as well, and two of the wheat strips. I also graze twelve cattle north of here, and have seventeen goats, but they are all on loan to Andrei as his crop was the least productive last year.”

Another spoke up, “And I have the strip adjacent to Leo. The orchard in the northeast cow pasture I have harvesting rights for this season. But the fruit is almost ripe, and once we harvest, the rest of the year I believe its Ivan and Matryoshka who have kindling rights to all the fallen leaves, twigs and branches for fuel this season. Then it goes to…who is it again?”

“Rogozin, I believe.” Chimed in another man.

“A yes, Rogozin, that’s it. I believe Rogozin and I swap strips next year now that you mention it, and two of mine will be let fallow for the next three seasons starting next winter. Though everyone will have grazing rights there in two seasons’ time. And I think I also have about twenty head of cattle, but this time of year they are in Smedyakov’s plot which is also fallow for two more seasons.”

Ivan’s eyes positively bulged out of his skull as he frantically tried to take notes of all this in his ledger. He had it filled with names scribbled in, arrows pointing between stick figures and crude sketches of plots and houses representing land and families, but he failed miserably in keeping up. “So none of you…owns…these plots?”

A wise old smile curled on Fyodor’s cracked lips, “Depends what you mean by own. Much of the land you see is owned by the Sheremetev family. Many men in this room are their serfs. Some of us are free peasant smallholders with a few hundred acres each. But the land is effectively communal, shared by all of us. And perhaps these community arrangements are what seem to be making your head spin”

“Hm, well our department is starting to create better bookkeeping around land ownership, cultivation, and productivity. This will help the Tsar apportion aide and relief more easily to you all in times of need.”

“And make it easier to levy grain tax!” Grunted an angry older man.

“Well, now, not necessarily. But we want to modernize Russia’s agriculture. I spent many months with our Tsar on his grand tour of Europe, and my, how they have modernized agriculture. In Prussia, they were averaging thousands of baskets of rye per acre. And the use of fertilizer! The output was incredible, just incredible. The efficiency.” Ivan let out a longing sigh.

The disgruntled man replied, “Well, as a farmer I’ve never experienced your average year. We experience too much rain one year, too little the next. A surplus, then a shortage. A fiery hot day in the summer and frost the next. You put all our holdings on your singular plots, and one crop failure would kill us all. Our strips, unproductive to you, distribute our risk, provide innumerable benefits. Tested over hundreds of years.”

“It is true.” Fyodor calmly followed up. “While we may sacrifice some of what you may call efficiency, we make up for in durability. Our little town didn’t lose a single man, woman, or child in the Time of Troubles. We may be backwards in your eyes, but this is perhaps from a lack of understanding, Ivan. With more time here, you would see.”

Ivan had gained a great respect for Fyodor over the course of his short visit, and somewhere inside of himself he felt that the old man was right on some deep and primordial level. But it is not what Ivan had learned over the course of his schooling and in the ministry. Not what he had seen in the great monocultural plots of Europe, which stretched clear out to the horizon in every direction, all with one simple owner, a single entry in an official’s ledger. “Well, yes, indeed. You all are excellent farmers, that much I have learned over the course of my visit. But I am sure that there are some small measures we can start to take to modernize. Think of the beauty, simplicity of each of you having large, uniform plots to tend, streamlined ownership, advanced tools and techniques for cultivation, and the ability of us to track this all in our department.”

“That all sounds grand, Ivan.” Fyodor said, patting him on the shoulder. “But perhaps you can visit more villages, take more notes, and see what small steps you can take that the Tsar sees fit, and that we see fit too.”

“Yes, yes, I agree. Wholeheartedly. Perhaps we start with last names. Even this has presented me with certain challenges on my visit.” He rifled through his large, overflowing ledger, found the relevant page, and ran his index finger down its length, “Three Luhzin’s, four Alexei’s, five Dmity’s, and there is me and Ivan, of course,” he added good-naturedly.

“Ok, Ivan. Well, do what you must tomorrow and we’ll all come out to see you off when you head back to Petersburg. We were honored by your visit.”

The meeting adjourned, and Ivan left the room, with just about everyone still surprised at the Ivans’ greenness, though Ivan remained relatively oblivious to it all.

Fyodor mused, “Well, it seems as though it will be some time, a generation or two, before Petersburg is competent enough to provide any help…or do us any serious harm. He-he-he.”

The grumpy villager from earlier piped up, “You say this now, Fyodor. But I will not have some incompetent Jew in the ‘intelligentsia’ help ‘fix’ the idiocy of rural life or whatever they will be calling it. We must push for a stop to these interventions.”

“Oh, come now. He came to church, he’s Orthodox!” replied another.

“And they barely can reach these towns, foolishly coming by carriage in the muddiest time of spring, I don’t think we have anything to fear.” Added Leo.

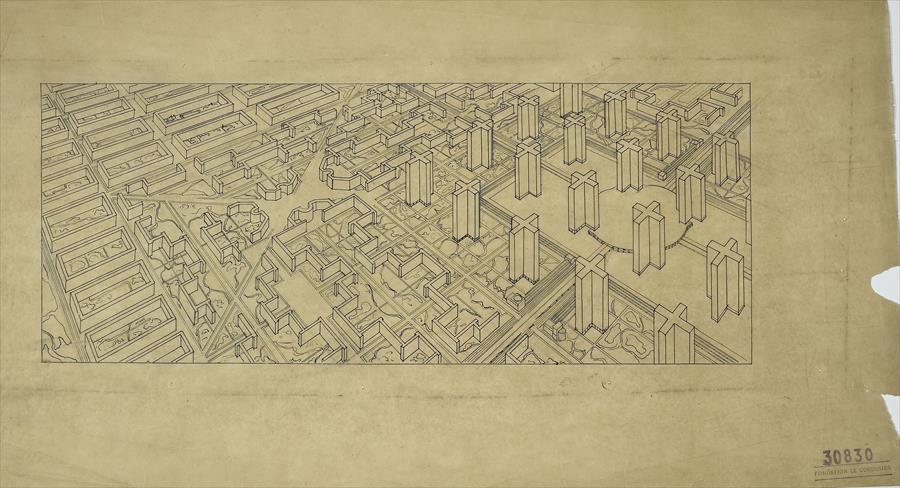

The next morning, Ivan frantically set about the final tasks of his trip. He was fussing about with a mess of stakes and twine, measuring and mapping out large plots of evenly-spaced rectangular grids. He stepped over veggies, through swamps and bogs, over rocky outcroppings, up hills, down hills, down into ditches, stubbornly tracing his straight lines over the countryside. The townsfolk watch him curiously all morning as they went about their tasks, either chuckling to themselves or shaking their heads in quiet disapproval. But by the time he was loaded into his carriage and said his goodbyes to the little village of Konevnya, Ivan was able to look down at page after page of the most perfect looking map of Konevnya, a rectangular little village made up of the most perfect, evenly-spaced rectangular grids of fields and lots that anyone had ever seen.