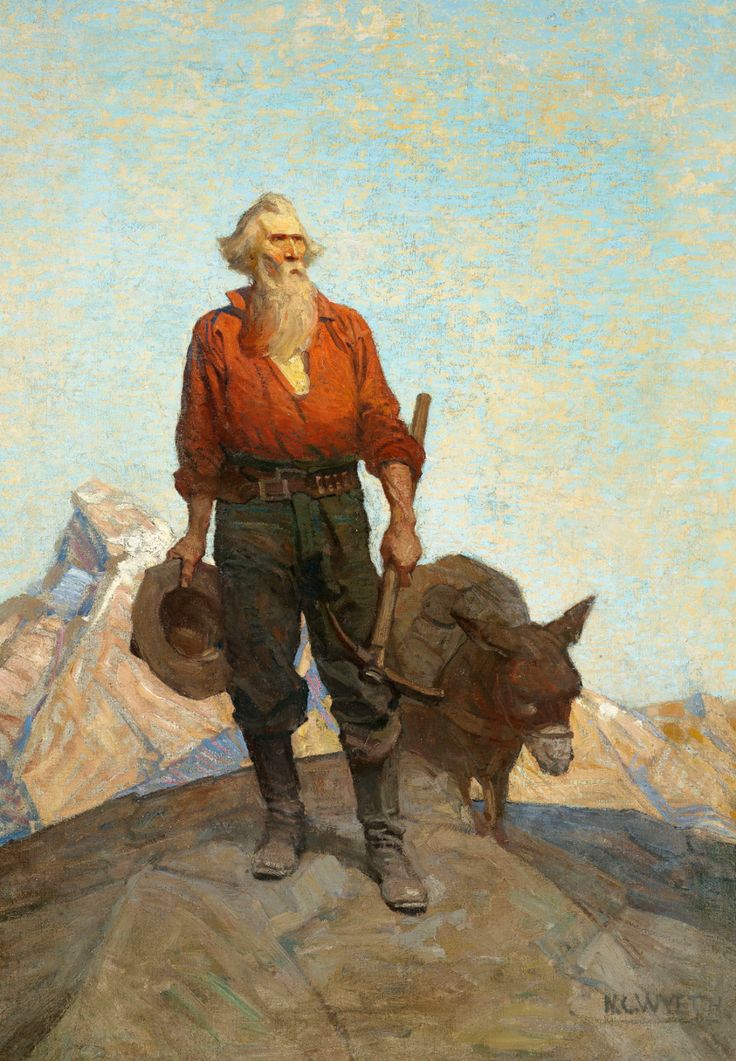

The Prospector

November 2024

The desert is either too hot or too cold. Too windy or not breezy enough. Too soaked through with monsoonal rains or too bleached by the hot summer sun. Rarely, if ever are the conditions just right. This is why it is so sparsely populated by plant and animal and man alike. But each hearty desert plant makes do, and displays its own unique, illogical and stubborn will to live. The small, fragile mouse and the emaciated, conniving fox both somehow make ends meet brutal year after brutal year, spiting the odds.

Despite all this, the desert occasionally rewards the hearty dessert traveler with a gift. The wind dies down. The sun peaks out from behind the clouds. He breathes in the sharp, cold air that almost burns his nostrils with its purity. He hears nothing but the soft coo of a desert songbird. He is alone alongside the stoic, uncomplaining plants.

The prospector stood tall, taking in one of these rare moments of desert bliss. His left hand gently tugged at his long white beard. It was not pure white, but tinged grey and brown from particulates, food scraps, and years in the bush. Stuck in this matted mane were foxtails and thistles. A sudden gust of wind picked up sand and pebbles, thrusting them violently into the prospectors face stinging his eyes and chapped lips with their force.

“Oh-he-he-he!” He bellowed, “the desert never let’s you enjoy those moments for long, eh Rocinante!”

He smacked his loyal mule on its hindquarters, and Rocinante gave an approving whinny. “Alright, we better get a’ movin’.”

Rocinante, slowly and with great power, put one hoof in from of the other, pots, pans and other heavy essentials clattering loudly with each step. The mule was ancient, yet somehow drew more power from the earth with each year. His muscles were taut and sinewy. He was trim but not emaciated as many mules in the desert are. His coat was short, but healthy, beginning to thicken in anticipation for a winter silently approaching. The prospector could guess the impending weather from Rocinante’s coat, much before temperatures, clouds, and flora yielded any hint of change.

The prospector matched or maybe even exceeded his sturdy mule’s strength. He stood proudly at six-foot, five-inches with legs like tree trunks. His forearms were as taut as Rocinante’s muscles, vascular and tireless, made so by years of swinging the pick and the shovel. During waking hours, his pick never left his hand, and at night it never left his side. He refused to strap the pick to Rocinante’s back with all the other gear despite it’s excessive weight (it sported a ten pound head), and he never knew why. It was just something he always preferred to carry. Like his mule, the prospector was approaching antiquity as well, but somehow his body and mind stubbornly refused to wither. Perplexingly, he had looked seventy for the past fifteen years, and was probably the fittest he’d ever been. He couldn’t tell you his age. He drew strength fro the desert. From the land. From his pick. From an idea.

The two made their way slowly, uncomplainingly for Panamint City. Or what was once Panamint City. The small mining town popped up nearly a decade back when silver and copper were found high up Surprise Canyon on the west flank of the Panamint Range in the Mojave. But the town was nothing more than ruins at this point. It was largely abandoned in ’96, and a flash flood took out most of what remained in the spring of ’97. But the ruins lay at the base of Panamint Pass, a tedious yet surefire way to get over the range and to the valleys that lay east. The prospector had actually lived in Panamint City for a few months years back. He didn’t care to stay for long. The straight rows of shacks, post office, and neatly laid our dirt tracks all suggested order, suggested a plan. But this facade of rationality was dwarfed by the town’s savage lawlessness. It was considered an evil place even among the ranks of the rugged, lawless men of the wild west.

The prospector couldn’t explain it, but he preferred the cosmic order of the wilderness to the facsimile of it that man attempted. He and Rocinante preferred to try their luck with the summer’s heat, the winter’s cold, the land’s brutality, the solitude, the snakes, the spiders, the mountain lions, than with the designs of fellow man.

Up and over Panamint Pass they plodded, eventually making it to the crest, beholding the infinite expanse of the Mojave, and then dropping down into Johnson Canyon, where the eccentric and enterprising Hungry Bill resided. Years back, Hungry Bill decided to make use of an unlikely perennial spring he found to grow a plethora of fruit trees, and thus Hungry Bill’s Ranch was born. He supplied produce to Panamint City in its heyday, and now sold to lonely travelers passing through. It was an unbelievable, if not impossible, sight to behold in the middle of the Mojave, the hottest and driest place on the planet. Hungry Bill’s was a veritable Garden of Eden for the lonely prospector who knew about this desert gem.

The two companions made it down and had the good luck of running into Bill, who was meticulously working to resuscitate a small tract of persimmons that struggled through the brutal heat of the summer.

“Bill, how the hell are ya?”

Bill looked up from his work, startled by the company, “Oh. I’m alive. And summer’s over. Where you two off ta? Haven’t seen you in what—years?”

The prospector grabbed his beard by its end, furrowed his chin into his chest, and peered down the bridge of his nose to assess its length. His beard was a rudimentary form of timekeeping, and it worked on the order of years with a margin of error on the order of years too.

“Musta been years, beard’s lookin’ pretty long. We’re headed off to the Funerals, got a good feelin’ ‘bout it out there, can’t explain. No one’ll be out their, neither. Ain’t that right Roci?” He gave the mule a firm pat on the shoulder. Rocinante whinnied and threw his head back in anxious excitement.

“Damn mule understands every word you say,” Bill said, chuckling, “damn miracle, that is. The Funeral Range, eh? Defnitly won’t be no one out there. Good volcanic rock too. Should find a nice cave to shack up in.”

“Hm,” the prospector grunted “can we have some fruit?”

“Watchya got?”

“No gold, no money. Been slim pickins’ lately. Pay ya on my way back west this spring.”

“You said that last time.” Bill scoffed incredulously, though he still drew a burlap sack from the pile of junk next to him, dumped some rusty irrigation hardware out of it, and stuffed it full of fruit. He walked over to the mule and fixed the bag to its back amidst the mess of other supplies.

“Good luck, pal.” Bill tipped his hat to the prospector and Rocinante.

“We’ll see ya this spring. C’mon boy.”

The prospector and Rocinante loudly clanked along down canyon and Bill went back to tending his grove, chuckling to himself “‘Pay ya when I’m back’ eh? Ha-ha.”

The prospector never had much luck out west. He struck enough to pay off the odd debt here and there. Enough to cover a week long fling in bars and brothels at just another nameless desert down destined for abandonment, to be nothing but dust, but he never did strike it big. Never gave up though. Fueled by an idea.

He was a young man of twenty nine when he set out from the Mid-Atlantic. He left the monotonous, predictable, rational life of an urban factory worker, clocking in and clocking out day after day after day for one of adventure and for the allure of a great fortune. Despite thirty or forty or fifty or who knows how many years of what most would call failure and destitution, he only seemed to get more content with it all. Don’t be mistaken, he swung his pick with a burning fury and a rapacious speed unmatched west of the Rockies. The prospector was not fueled by gold, or rhyolite, or bauxite, or Bill’s fruit, or by anything except for an idea that stubbornly refused to die.

Perhaps this is what kept him warm all winter in that forlorn desert cave in the Funerals. Despite the wind and the snow and the biting cold and the wholly insufficient tattered cotton blanket he slept under. Despite the lack of water, the moldy fruit, the age, the aching muscles. Despite all this, he slept soundly each night, kept warm by an idea.